2.6 Dutch Landscape Painters in Rome

We left the Dutch landscape painters just as Claude Lorrain appeared in their midst.1 That was in 1625 (if we disregard the ‘dark’ period in Tassi’s studio). Cornelis van Poelenburch had already left Rome but Bartholomeus Breenbergh stayed on for a few more years. Two years later, in 1627, we come across a little house in the Strada Margutta which is home to Claudio Lorense, pittore, con un suo compagno fiamengo [painter, and his Flemish companion]. It is not hard to guess who this compagno is. A clue is provided the following year by the mention of his first name: Enrico fiamengo pittore. This companion is Herman van Swanevelt (c. 1603-1655), who had probably moved to Rome from Paris a few years earlier.2 He was called ‘Heremyt’ because of the very sheltered life he led.3 Though not by nature a revolutionary of any sorts, he nonetheless marks the beginning of a new stage in the ‘yearning for Italy’ felt by Dutch landscape painters. He saw Italy through Claude’s eyes and endeavoured to render his experience of the landscape in the form of a classically balanced composition under the same sunny light of the south and in painstaking adherence to his revered model [1-2].4 Swanevelt’s art was certainly little more than mediocre at best.5 But his etchings – even more than his paintings – have enchanted Romantics of all ages [3]. 6 They were the measure of all things for the Germans Koch and Reinhart, and Goethe thought more of his series of Roman vedute than he did of Piranesi’s etchings!7 In 1637 Swanevelt returned to Paris, where he was given the honorary title of ‘Herman d’Italie’. He adhered consistently to the example set by the great Claude, whose art undoubtedly gained in significance in his native country thanks to the efforts of this intermediary. At all events there was no dearth of honours for Swanevelt in Paris.8

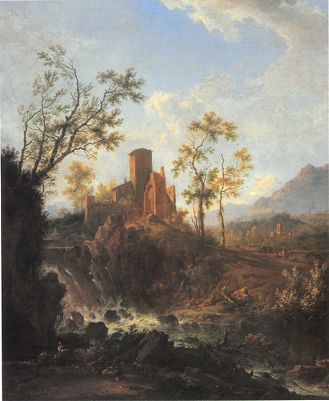

Almost a decade later Jan Both (1615/22-1652) arrived in Rome. He, too, was enthralled by Claude’s sublime landscape art.9 Both had a more pronounced sense of light and colour than Swanevelt, for whom composition was of overriding importance. A group of trees with dense foliage penetrated by rays of sunlight on one side of the picture and a view of the Campagna countryside set against a backdrop of mountains shimmering in a bluish-grey haze on the other side constituted the main elements of his mood landscapes [4]. A lone wanderer or a shepherd couple driving their animals through a ford convey a sense of a happy, carefree life. Dutch collectors adored such Arcadian images, just as the generation before them had appreciated the mythological idylls of Poelenburch and of all the fijnschilders who imitated him. Jan Both returned to Utrecht in 1642 and the impact his Claude-inspired style had on Dutch artists and contemporary tastes can hardly be overestimated.10

1

Claude Lorrain

View of the Campo Vaccino (Forum Romanum), c. 1636

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 4713

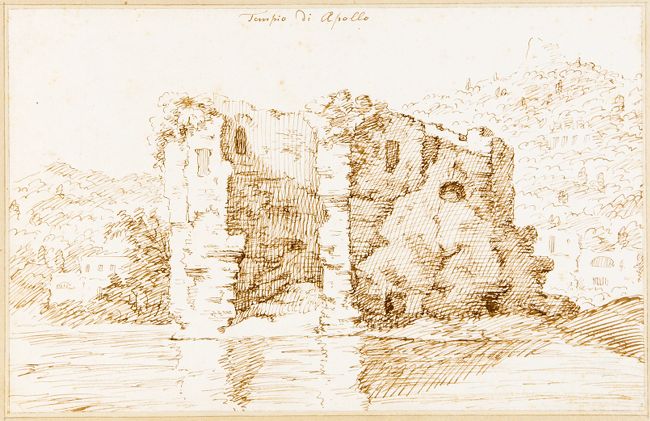

2

Herman van Swanevelt

Campo Vaccino (Forum Romanum), Rome, dated 16[3]1

Cambridge (England), Fitzwilliam Museum, inv./cat.nr. 367

3

Herman van Swanevelt

Balaam and the donkey with the angel

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1892-A-17462

4

Jan Both

Italianate mountain landscape with figures, c. 1645

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG956

Houbraken includes Jan Asselijn (c. 1610-1652) among those who brought Claude’s luminous style to Holland. We take a different view nowadays and feel that it was Asselijn, in particular, who gave artistic expression to the personal experience of the Italian landscape [5].11 He worked from 1641 to 1645 in Rome and his paintings must have been very popular in Italy, given that Sandrart mentions their inclusion in collections in Rome and Venice.12 In 1642, Jan Baptist Weenix (1621-1659) and Nicolaes Berchem (1621/2-1683) entered the Eternal City together.13 Karel du Jardin (1626-1678) arrived not much later,14 so in the first half of the 1640s Holland’s top four landscape painters were in Rome together. Berchem may have gone to Rome a second time between 1653 and 1655,15 while Karel du Jardin was back in the city in the 1670s in the company of the art dealer and collector, Gerard Reynst.16 Apart from the bucolic landscapes [6], we are familiar with du Jardin’s portraits [7] and biblical scenes [8], some of which date to this late period. In the case of Karel du Jardin there is also clear evidence of the continuing influence of Pieter van Laer’s art, which may have been passed on by Michiel Sweerts. Weenix lived a good life in Rome. He found a patron in Cardinal Giovanni Battista Pamfilj, the later Pope Innocent X, whose commissions kept him busy for four years. None of his works from this period have survived, however [9].17 Nicolaes Berchem was certainly the most prominent of the four artists [fig. 46] [10]. His was astonishingly prolific and highly creative in inventing ever new Italian motifs. The example he set was a constant source of enthusiasm, especially in the 18th century. The French led the way here but Northern Italian landscape painters, too, had an open eye for the beauty of Berchem’s idylls – a subject to which we will return later.

5

Jan Asselijn

Italiaaans havengezicht met ruïne

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 950

6

Karel du Jardin

Southern landcape with a sheperd and animals, c. 1660-1664

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 404808

7

Karel du Jardin

Portrait of a man

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-191

8

Karel du Jardin

Paul and Barnabas heal a cripple, dated 1663

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK A 4922

9

Jan Baptist Weenix and Pasquale Chiesa

Fantasy Landscape of an Oriental Seaport, with Rider on a horse, c. 1645-1646

Rome, private collection Galleria Doria Pamphilj, inv./cat.nr. FC 581

10

Nicolaes Berchem

Laban divides the work

Munich, Alte Pinakothek, inv./cat.nr. 440

Although this quartet was followed by other artists and they in turn by yet others, few fundamental changes occurred over time in this tradition of landscape painting, which was largely shaped by Both and Berchem. The artists returned home with full sketchbooks, which stood them in good artistic stead for the rest of their lives. Others who found the long journey to Italy too daunting used the studies made by those who did go so skilfully that it is often impossible to distinguish between the ‘genuine’ and the ‘pseudo’. Of the many artists on whom the Italian sun shone we can mention only the better known. Among the artists present in Rome in the 1640s were Hendrick Mommers (1619/20-1693), Hendrick Verschuring (1627-1690), Johannes Lingelbach (1622-1672) [11] , who travelled together with Jan Worst (died in or after 1686) [12], Willem de Heusch (c. 1625-1692) [13],18 Adam Pijnacker (1621/2-1673) [14], Matthias Withoos (c. 1627-1703), Jacob van der Does I (1623-1673) [15], Willem van Bemmel (1630-1708) [16], Hendrik Sonnius (c. 1615-c. 1688),19 Thomas Wijck (c. 1616/21-1677) and Jan Wils (1602-1666) [17]. 20

11

Johannes Lingelbach

Roman market scene, between 1644 and 1650

Karlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, inv./cat.nr. 2571

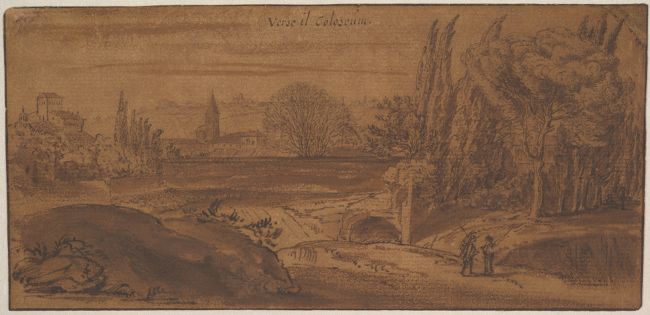

12

Jan Worst

View of the ruin of the Colosseum

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-T-1884-A-388

13

Guilliam de Heusch and possibly Jan Both

Italianate landscape with fisherman near a waterfall, dated 1641

art dealer art dealer

14

Adam Pijnacker

Landschap met herders en vee, c. 1645-1655

15

Jacob van der Does (I)

Shepherd with herd of goats in front of a farmhouse with a tower (verso: sketches of a southern landscape and a Roman tomb), dated 1646

Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle, inv./cat.nr. 21842

16

Willem van Bemmel

Italianate riverlandscape with hunters resting

Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, inv./cat.nr. Gm 393

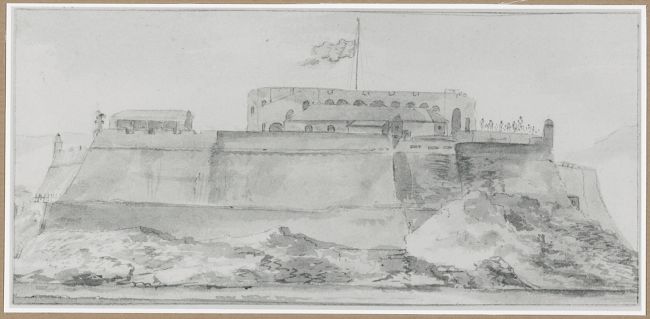

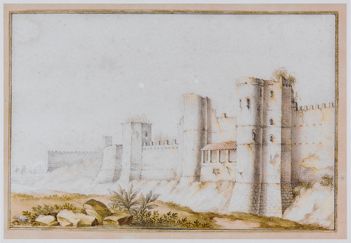

17

Jan Wils

Castel Nouvo, Napels, c. 1655-1656

Frankfurt am Main, Graphische Sammlung im Städelschen Kunstinstitut, inv./cat.nr. 2199

We met a number of them of them earlier on their outward journey in Lyon, where they formed a merry little group.21 Anthonie Waterloo was probably among those who made their way to Italy via Lyon, although we have no firm evidence that he actually arrived in Rome. Weyerman called Jacob van der Does the Dutch Benedetto Castiglione. Houbraken thought the paintings he made in Rome were mostly inspired by Pieter van Laer, but there is little tangible evidence to support that assumption. The Fleming Anton Goubau (1616-1698), by contrast, was completely at home among the Dutch genre painters in Rome.22 He was one of one mind with Berchem and Dujardin, as if he hailed from Haarlem rather than Antwerp (fig. 1/3) [18]. Sonnius was a pupil of Pieter Monincx and is probably identical with the artist who occupied the position of landscape artist to the Pope in Rome [19-20].23 Hendrick Verschuring (1627-1690) stayed for roughly ten years (1647-1657) in the Eternal City and when he was in Paris on his way home he met the son of the burgomaster ‘Maarzeveen’ who persuaded him to embark on a second trip to Italy and so he spent three more years there [21-22].24 When in Rome he encountered the members of a younger generation, among them Adriaen van de Velde (although doubts have been raised as to whether he was actually ever in Italy),25 Willem Romeyn (c. 1625, in or after 1695) [23], a pupil of Berchem and du Jardin,26 and Frederik de Moucheron,27 who had just finished his apprenticeship under Asselijn.

18

Anton Goubau

Roman ruins

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 142

19

Hendrik Sonnius

Italianate landscape with two travellers and a small temple, dated 1647

Haarlem, Teylers Museum

20

Hendrik Sonnius

Southern landscape with an inn near ruins, dated 1645

21

Hendrick Verschuring

Southern Landscape with Praying Pilgrims, Hunters and Travelers at a Chapel, dated 1650

Private collection

22

Hendrick Verschuring

View of the Campo Vaccino (Forum Romanum) in Rome, dated 1651

23

Willem Romeyn

Italianate mountainous landscape with a shepherd and a shepherdess with their animals at the entrance of a cave, after c. 1651

24

Bartholomeus Appelman

Italianate river landscape, dated 1671

Vienna, Vaduz, Valtice (Czechia), private collection Fürst von Liechtenstein

A group of travellers comprising Bartholomeus Appelman (1628/9-1686/7) [24-25], Petrus Vignois and Carel Codde (1625/30-1683) [26] had departed from The Hague around 1650.28 Appelman later appeared in Rome in the company of Philips le Petit (c. 1631/2- in or after 1670) and Willem Doudijns (1630-1698), but there is no trace of the other two. Vincent Laurentsz van der Vinne (1628-1702), who set out on a long journey in 1652, must have arrived in Northern Italy at that time or on some other occasion, although there is nothing in his diary to confirm this. Houbraken recounts that he was in Genoa, which is confirmed by Northern Italian views found on the back of entries in his diary.29

The style the Dutch used to convey their image of Italy, which gradually spread throughout Europe, was particularly popular among German artists. Johann Heinrich Roos (1631-1685), who in 1647 was sent to be apprenticed to Guilliam, the father of Karel du Jardin, in Amsterdam, travelled to Rome three years later, where he will have felt completely at ease among the circle of Dutchmen.30 At all events, his paintings can barely be distinguished from those of his Dutch contemporaries. His son, Philipp Peter Roos (1655/7-1706), was even a member of the ‘Bent’, which christened him ‘Mercurius’, because of the speed with which he painted.31 He lived in a ruin near Tivoli, rarely ventured into the city and never returned to Germany [27]. The numerous pictures made by this Rosa di Tivoli, as the Italians called him, were to be found everywhere.32 He demonstrated little ingenuity in his adaptations of Berchem’s Romantic ruins which he sold to the general public. The much-travelled Christian Reder (1656/61-1729), who settled in Rome in 1686, also paid homage to Berchem in his idyllic pastoral images [28].33

25

Bartholomeus Appelman

View of Tivoli, c. 1650-1657

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

26

Carel Codde

Travellers in Italian landscape, dated 1669

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. C.Codde 1

27

Philipp Peter Roos

Shepherd with a dog, billy goat and two wheel, c. 1685

Prague, Strahov Monastery, inv./cat.nr. 503

28

Christian Reder

Shepherd with herd

Rome, private collection Galleria Doria Pamphilj

The picture gradually changed in the 1660s and 1670s. Berchem’s lively pastoral images came to be replaced by classically composed landscape paintings inspired by Nicolas Poussin and Gaspard Dughet. The classical-style staffage of the pale-coloured images was directed more at the mind than at the eye of the beholder. The three Glaubers – Johannes (1646-c. 1726), Johann Gottlieb (1656-1703) and Diana (1650-after 1721) – Albert Meyering (1645-1714) [29], Jacob de Heusch (1656-1701) [30] and the brothers Adriaen (1630/31-1705) [31] and Engel van der Kabel (1640/1- after 1695), all of them highly regarded masters in their time, serve as good examples of this new style and many more could be added to the list, including Adriaen Honinch (1643-after 1683) [32],34 Jan (1654-1727) and Jacob van Bunnik (died 1724), Nicolaes Piemont (c. 1644-1709) [33] and Jan Blom (c. 1621/2-1685) [34].35 While their number could certainly be augmented, this is not the place to do so. The disadvantage of such a brief periodical overview is that it obscures the different directions in which landscape painting was moving at any given time. Many artists (such as Hendrick Verschuring and Johannes Lingelbach) loved to portray daily life in port towns and cities; Adam Pynacker was intrigued by the motif of a river valley at twilight; a third group of landscapists betrayed the lingering influence of the Bambocciate, while others embodied the very long-lasting influence of Claude Lorrain.

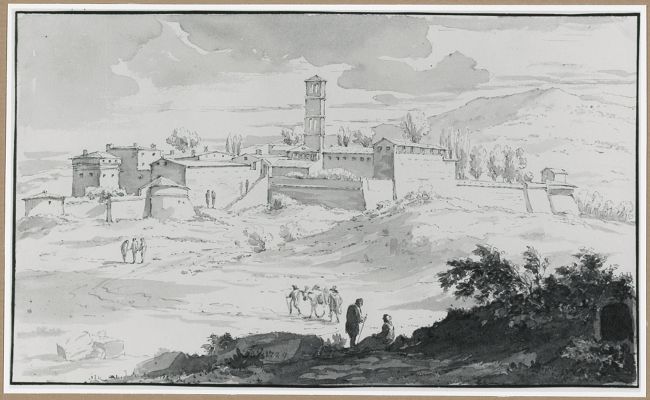

29

Albert Meyering

View on Genazzano from the north-east, c. 1675-1687

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 8115

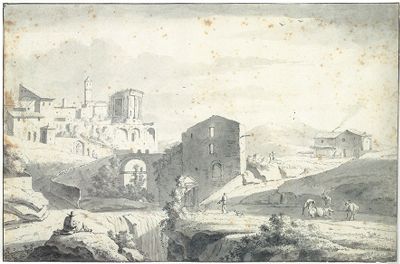

30

Jacob de Heusch

View of the Campo Vaccino (Forum Romanum) in Rome, with the Colosseum and the temple of Venus, dated 1694

Private collection

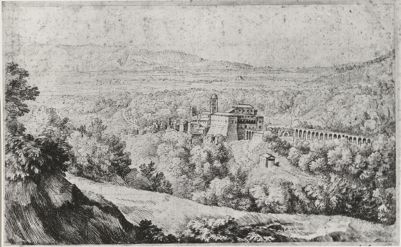

31

Adriaen van der Kabel

The Ponte Molle (Milvio) in Rome, c. 1659-1666

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. Z. 518

32

Adriaen Honich

Bridge with stone arch and rocks at a stream in Tivoli, c. 1667-1683

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 10893

33

Nicolaes Piemont

Southern landscape with shepherds and animals at a waterfall

34

Jan Blom

View of the Farnese gardens in Rome, dated 1652

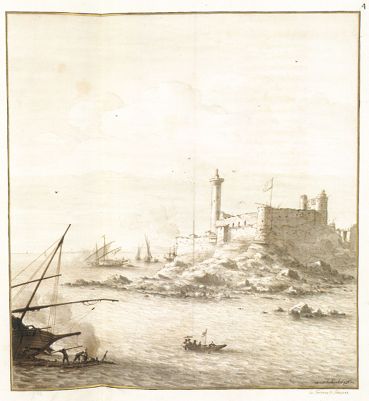

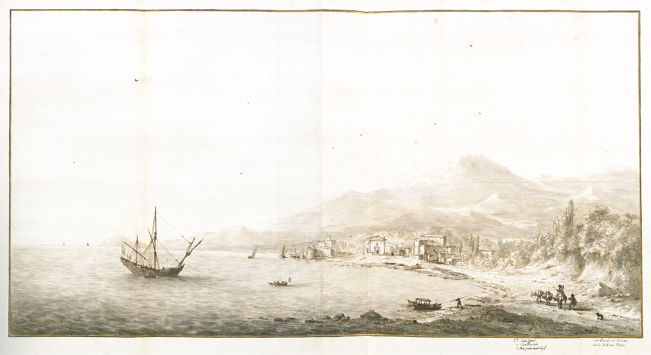

Finally, we can pinpoint a separate group of painters and draughtsmen who renounced animal landscapes in favour of a return to Italian vedute. The draughtsmen included Vincent Laurentsz van der Vinne and Jan Haeckert (1628-1685)36 and, in particular, Willem Schellinks (1623-1678) who, in the course of a lengthy journey he undertook in 1665 with Jacques Thierry, the son of an Amsterdam merchant, travelled the length and breadth of Italy, including Sicily [35-37],37 and even went to Malta.38 He made his way from Naples to Rome in the company of Frédéric Kerseboom (1623-1693), G. Sabé, Alexander Le Petit (c. 1612-1658/9) and N. Donkers.39 A number of topographical drawings made by his brother, Daniel Schellinks (1627-1701), have survived [38].

The gentle brush drawings of Jacob van der Ulft (1621-1689) and Jan de Bisschop should not be overlooked. Houbraken claims that van der Ulft never set foot in Italy, but the many lively drawings with topographical inscriptions could not possibly have been made after engravings following his return home.40 Landscape sketches alone were not enough to satisfy Jan de Bisschop (1628-1671). In 1668/9 he published a volume entitled Signorum veterum icones.41 In compiling this book he availed himself of ‘de gunst von goede vrienden, die de zelve (schetsen) te Rome geteekent hadden’ [the favour of good friends who made sketches in Rome]. These colleagues and friends were Pieter Donker (c. 1635-1668), Willem Doudijns (1630-1698), Jacob Matham (1571-1631), Dirck Ferreris (1639-1693), Jacob Neeffs (1610-after 1660), Adriaen Backer (c. 1636-1684) and Nicolaes Wilingh (c. 1640-1678).42 However, we know for certain that Jan de Bisschop was in Italy too.43

35

Willem Schellinks

Landscape with the Stromboli vulcan, after 1665

Caen, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Caen

36

Willem Schellinks

Castello Maniace, Syracuse, c. 1665

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, inv./cat.nr. +Z116011509

37

Willem Schellinks

Pozzalo from the east, c. 1665

Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, inv./cat.nr. +Z115157004

38

Daniël Schellinks

View on Tiber at Trastevere with Tiberisland, 1660s

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 10028

The dryly executed pen-and-ink-drawings of Roman views by Jan van Call (1656-1706) [39-40] and the Fleming, Lieven Cruyl (1634-1720) [41-42], appear to have been made to satisfy lovers of classical antiquity rather than lovers of art.44 The end of the century witnessed a surge of archaeological interest in the world of Roman ruins. Bonaventura van Overbeek (1660-1705) was an enthusiastic draughtsman after antiquity [43]. His major work on the Roman ruins, the fruit of long years of study, was published in 1708, a year after his death, by Michiel van Overbeek (1670-1729), a series of whose topographical drawings has come down to us [44].45 Isaac de Moucheron (1667-1744), who visited Rome between 1694 and 1697, also produced some very fine drawings of the city [45-46]. 46 His paintings, by contrast, are more in the classical style of Nicolas Poussin [47].47 The vedute lived on in paintings, initially in a fanciful and Romantic form, such as in the harbour paintings of the brothers Jacobus and Abraham Storck and in compositions that reflect Beerstraaten’s impressions of Italy [48].48 Johannes (c.1615/6-1686) and Hendrick Danckerts (c. 1625-1679/80) may have familiarised themselves with vedute in Italy, later taking such views to great perfection in England [49].

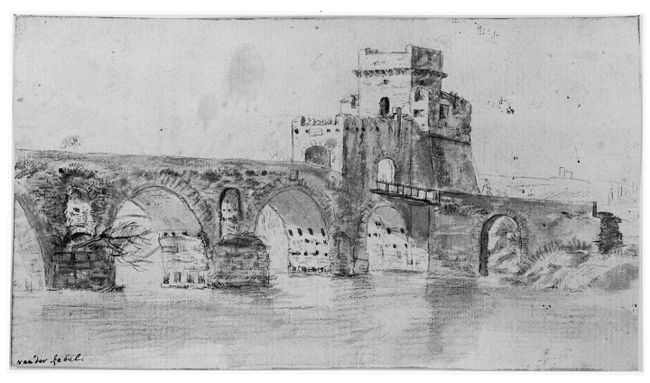

39

Jan van Call (I)

View of Rome's Aurelean city wall, c. 1680

Nijmegen, Museum Het Valkhof, inv./cat.nr. 2004.271

40

Jan van Call (I)

View of Rome's Aurelean city wall, c. 1680

Nijmegen, Museum Het Valkhof, inv./cat.nr. 2004.270

41

Lieven Cruyl

View of St Peter's in Rome, 1664-1678

42

Lieven Cruyl

View of Castel Sant 'Angelo, Rome, 1664-1678

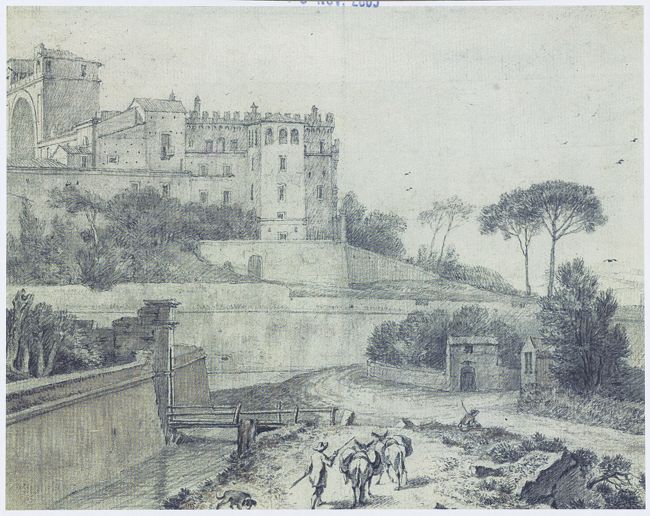

43

Bonaventura van Overbeek

Ruins of the so called Apollo temple at lake Averno, near Pozzuoli

Private collection

44

Monogrammist MVO (formerly called Michiel van Overbeek)

View in Rome near the Colosseum, after 1667

New York City, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 2011.225

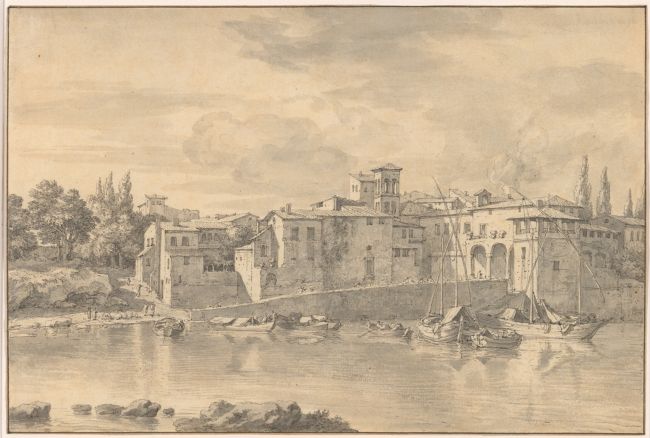

45

Isaac de Moucheron

A view of the Porto di Ripa Grande from the southeast, Rome, c. 1708

Brussels, Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, inv./cat.nr. 4060/2626

46

Isaac de Moucheron

View of the Blvedere, Rome, after 1694

Oegstgeest, private collection J.A.M. Smit

47

Isaac de Moucheron

The Tiber with a view of Ripa Grande, late 1690s

Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie, inv./cat.nr. M.Ob.1023 MNW

48

Jan Abrahamsz. Beerstraaten

Imaginary view of a port with the Santa Maria Maggiore, dated 1662

Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv./cat.nr. 1030

49

Johannes Danckerts (I)

Italianate landscape with figures near a waterfall, dated 1677

50

Caspar van Wittel

Rome, Piazza del Popolo, dated 1680

Berlin (city, Germany), Gemäldegalerie (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. Z 11615; cat. Bock 1921, p. 370, als Anoniem 17de eeuw

More important for our purposes, however, is Caspar van Wittel (c. 1653-1736), known as Vanvitelli, from Utrecht, since he re-established the connection with Italian art.49 Among his first works in Rome were his illustrations for a hydraulic engineering plant devised by Cornelis Meijer (1629-1701), who planned to make the Tiber navigable. The manuscript for this work was completed around 1677 and the title page bore van Wittel’s name, to which were added the words: ‘olandese in Roma, ne’ primi anni che da giovane vi venne da Olanda’ (a Dutchman in Rome who came here from Holland as a young man).50 He was already a member of the ‘Bent’ by the time of Abraham Genoels’ (1640-1723) baptism ceremony in 1675.51 A few years later van Wittel began painting Roman views in the light, lucid manner which the Berckheydes and Jan van der Heyden had perfected in his native country [50-52].52 In Palazzo Venezia [Rome] there is a large watercolour on parchment from 1683 showing Castel Sant’Angelo as well as large undated canvases with views of Rome [53]. The faithful topographical rendering of a city distinguishes van Wittel from the Roman painters of ruins who were fond of portraying such remains in painterly fashion at the onset of dusk. There can be no doubt whatsoever that in the 18th century Giovanni Paolo Pannini and Giovanni Battista Piranesi looked to van Wittel for inspiration the moment they began painting vedute.

51

Caspar van Wittel

View of the Arch of Titus, c. 1688-1695

52

Caspar van Wittel

View of Venice from the Island of San Giorgio, dated 1697

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P000475

53

Caspar van Wittel

View on Castel Sant'Angelo in Rome, dated 1683

Rome, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica (Rome), inv./cat.nr. 1408

The Venetian vedute painters also drew on him, especially Luca Carlevaris (1663-1730) [54] who spent some time in Rome.53 Van Wittel must have visited Venice at the end of the century, confirmation being provided by a view of the Fondamento inscribed and dated 1697 [55]. It is only a short step from here to Canaletto [56], as Mariette noted as early as 1714: ‘il (Canaletto) a travaillé dans la manière de v. Vittel, mais je le crois supérieur’ [he (…) worked in the manner of van Vittel, but I think he surpasses him]. Today van Wittel’s fame has all but faded away, which makes such an historically correct observation seem a little strange. During his stay in Venice he produced a delightful picturesque view of the Canale Grande, now kept in the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj in Rome [57]. Shortly after the turn of the century van Wittel spent a number of years at the court of the Duke of Medina Coeli in Naples.54 While there are plenty of drawings and paintings which date from this period [58], there is no indication that he exerted any influence on painting in Naples. In 1713 the artist was back in Rome and thereafter was regularly appointed to the position of director or curator of the foreign members of the Academy. As a draughtsman he was by no means just an accurate topographer. There are some brilliantly dashed off drawings with a with sheer brilliance which in the past were occasionally attributed to Claude Lorrain. The Berliner Kabinett has a large number of such drawings [59].55 Van Wittel was also one of the first to employ the gouache technique which became popular at that time.56 Theodor Wilkens, who was in Rome in the first half of the 18th century, drew similarly lively Italian views [60].57

54

Luca Carlevaris

The official entry of Henri-Charles Arnauld de Pomponne, known as the Abbé de Pomponne, into Venice as French ambassador on 10 May 1706, 1706-1707

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-C-1612

55

Caspar van Wittel

View of Venice from the Island of San Giorgio, dated 1697

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. P000475

56

Canaletto

View of the Grand Canal from the Salute towards the Carità, c. 1730

Hampton Court Palace (Molesey), Royal Collection - Hampton Court, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 400519

57

Caspar van Wittel

View of the Grand Canal from the Punta della Dogana and the Santa Maria della Salute, between c. 1694-1710

Rome, private collection Galleria Doria Pamphilj, inv./cat.nr. 239

58

Caspar van Wittel

View of the Villa Martinelli at Posillipo, Napels, after 1699

59

Caspar van Wittel

Arcadian landscape with sheperds, 1710s

Berlin (city, Germany), Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, inv./cat.nr. KdZ 30133

60

Theodoor Wilkens

Italian view, 1729 (dated)

Frankfurt am Main, Graphische Sammlung im Städelschen Kunstinstitut, inv./cat.nr. 3894

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] See p. 150 and the listed literature [§ 2.2].

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hoogewerff 1938, p. 71-73. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] The Flemish painter named ‘Enrico‘ who shared lodgings with Claude Lorrain is no longer thought to be Swanevelt. The first record which shows Herman living in Rome dates from 1629, when he lived in the parish of San Giuseppe a Capo le Case. Russell 2019, p. 34-35 . Swanevelt may have arrived somewehat earlier, about 1627-1628.

3 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Although Passeri described him as not very sociable and as being suspicious, numerous contemporary documents seem to indicate that Herman did not lead a sheltered life. See Russell 2019, p. 37-38.

4 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] In 1965 Blankert was the first to observe that in the 1630s Claude was also influenced by van Swanevelt, as can be seen in the paintings of the Forum Romanum (Blankert/Adams 1965/1978, p. 19-20, 101-102) illustrated above.

5 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Gerson’s negative remark on Swanevelt’s painting is in line with the current opinion in art history at the time regarding the Dutch Italianate landscape painters, who were criticized for lacking ‘Dutchness’. The exhibition Dutch 17th Century Italiante Landscape Painters in Utrecht in 1965 caused a revaluation of this group. About the appreciation of Swanevelt: Blankert 2007, p. 16-18.

6 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On van Swanevelt as an etcher: Steland 2005; Wuestman 2007. On Swanevelt’s paintings and drawings: Steland 2010.

7 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Goethe 1816-1817/1885, p. 460.

8 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Szanto 2003.

9 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Both: Waddingham 1964; Burke 1976.

10 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Jan Both presumably left Rome after 29 April 1642, when he is being paid 60 scudi for two landscapes painted for Cardinal Antonio Barberini (Lavin 1975, p. 8, doc. 61).

11 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Asselijn: Steland 1971.

12 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Sandrart 1675, vol. 2, p. 310. Nowadays it is often assumed that Asselijn was already in Rome in 1636; he left Amsterdam shortly after 4 November 1635, when he witnessed the christening of a son of his brother Abraham (Steland-Stief in Saur 1992-, vol. 5 [1992], p. 458).

13 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Jan Baptist Weenix and his sojourn in Rome: Wagenberg-ter Hoeven 2018, esp. p. 23-27. Instead, it is highly doubtful that Nicolaes Berchem ever undertook a trip to Italy. It has often been assumed that Berchem was in Italy around 1651-52 (Blankert 1965/1978, p. 147, note 11, repeated by other authors), but Biesboer dismissed this hypothesis on valid grounds (Biesboer 2006, p. 21-23).

14 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] No archival documents have been traced that can shed light on Karel’s first sojourn in Rome. Hoogewerff suggested that he was in Rome between 1642 and 1647 (Hoogewerff 1952, p. 93). According to Mandrella, he was possibly in Rome in 1653 (Mandrella 2012, p. 190). See also Schatborn 2001, p. 155 (in Rome ca. 1652-55).

15 [Gerson 1942/1983] Von Sick 1930, p. 8 and 68, thought a third travel was plausible, which has been dismissed by Hoogewerff.

16 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On March 24 1675 Du Jardin left for Texel, to travel on August 2 by ship to Italy, together with Gerard and Abraham van Reynst, younger brothers of Joan Reynst (1636-1695) and sons of the collector Gerard Reynst (1599-1658) (Bikker 2009). Du Jardin reached Rome late 1675; he is documented there in 1675, 1676 and 1678 (Kilian 2005, p. 14).

17 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Van Wagenberg-Ter Hoeven 2018, p. 24-27, 124 (cat.no. 30), 294, cat.nos. 145-148) mentions five works (all in RKDimages), four of which are executed in collaboration with Pasquale Chiesa. These paintings were made in the years in which both Giovanni Battista Doria Pamphilj (who became Pope Innocent X in 1644) and his nephew Cardinal Camillo ordered paintings from Jan Baptist Weenix. In the context of our project Maartje Visser found two more works made in collaboration with Pasquale Genovese in the Pamphilj collection, as well as several references to paintings by Weenix in Roman collections of the 18th century (Visser forthcoming).

18 [Gerson 1942/1983] In case he is identical with Guglielmo de Us, who appears on 14 November 1636 in the ledgers of the Academy (Hoogewerff/Orbaan 1911-1917, vol. 2, p. 51) he must have begun his Italian trip at an early age.

19 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] In the Liber Mortuorum of the parish of Santa Maria del Popolo there is a reference to a certain ‘Henricus quondam Henrici Zonii, Aghensis‘ who died on 28 September 1649 at the age of approximately 26 (Hoogewerff 1942, p. 73). His profession is not specified, however, and Hoogewerff suggested to read his name as Hendrik Hendrikszoon (Ibid., p. 73 note 1). Nevertheless, we can not completely exclude that he is the author of the drawing mentioned in note 249.

20 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Of this group only Johannes Lingelbach and Matthias Withoos are mentioned in the Roman archives. The presence in Rome of painters such as Jacob van der Does and Hendrick Verschuring is documented through the autograph inscriptions on some of their drawings and the accounts of their early biographers. In the case of Thomas Wyck, it is the combination of an Italian subject and the use of Italian paper that provides concrete evidence of his presence in Italy and therefore confirms Houbraken’s account that the artist used to make drawings of Italian buildings ‘from life’ (Schatborn 2001, p. 119).

21 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Gerson 1942/ 1983, p. 50-52. For Dutch and Flemish artists in Lyon: Ternois 1976.

22 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Bodart 1970, vol. 1 , p. 432-440.

23 [Gerson 1942/1983] Bredius 1889, p. 267. There is a drawing of a Roman landscape, dated 1647, in the collection of Prof. J.Q. van Regteren Altena (Van Regteren Altena 1930). [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] The drawing, inscribed ‘henritio zonius fl. 60 / Roma 1647’ is now in the Teylers Museum, Haarlem. Gerard Hoet suggested that Pieter Moninckx - rather than Sonnius - worked as painter of landscapes and buildings for the Pope (‘Lantschap- en Gebouschilder van den Paus’), but there is no evidence whatsoever to corroborate this (Hoet 1751, p. 90).

24 [Gerson 1942/1983] Probably Joan Huydecooper Jr., Heer van Maarseveen (1625-1704). [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Almost certainly Verschuring’s trip to Italy and France lasted not more than four or five years. He left Gorkum after 12 September 1647 and was certainly back in his hometown in 1652, when he joined the local ‘Broederschap der Romeinen’ (Tissink/De Wit 1987, p. 60).

25 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] There is no information to suggest that Van de Velde did travel to Italy. His Italianate views are based on the works of Nicolaes Berchem, Karel du Jardin and Pieter van Laer. See for instance Van Eerenbeemd 2006.

26 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Romeijn: Hoogewerff 1942, p. 123, 124- 126 (documented in the parish of San Lorenzo in Lucina in 1650 and 1651); Schatborn 2001, p. 147-151.

27 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] De Moucheron rarely represented recognizable places in Italy, and it was thought for this reason that he never pushed his journey further than France. In the light of the drawings of the Atlas Van der Hem at the National Library of Vienna, however, it must be conjectured that he travelled along the Mediterranean coast. Some of these drawings represent sites of the Moroccan, Italian, and even Greek coast, very rarely visited by artists in the 17th century, which strongly suggests the artist has seized them in situ (Alsteens/Buijs/Mathot 2008, p. 291-300).

28 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Bredius 1915-1921, vol. 7, p. 3-4.

29 [Gerson 1942/1983] On the diary: Gerson 1942/1983, p. 48; drawings in the collection of Prof. J.Q. van Regteren Altena. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Houbraken mentions that van de Vinne was in Geneva, not Genoa. As far as is known, Van der Vinne never travelled to Italy. On the diary: Sliggers 1979; Alsteens/Buijs/Mathot 2008, p. 271-278.

30 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] The supposed trip to Italy (1652-1653) probably never took place. See Gerson/Van Leeuwen 2017, § 5.2.

31 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] See Gerson/van Leeuwen 2017, § 5.2.

32 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Philipp Peter Roos is known to have worked for the art dealer Pellegrino Peri, whose inventory listed more than 70 pictures by Roos (Lorizzo 2006, p. 355-356).

33 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Reder’s position in the Roman art market: Pascoli 1730-1736/1965, vol. 2, p. 356-357; Spear 2010, p. 45.

34 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Honich: Roetlisberger 1963.

35 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Unlike the other painters mentioned here, Jan Blom presumably never set foot in Italy. Many of his paintings contain classical elements that are drawn from 17th-century prints after the antique. See Riccomini 2018.

36 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Also Jan Hackaert probably never went to Italy, although he extensively travelled in Switzerland. According to Luuk Pijl a trip to Italy is neither documented, nor likely (Saur 1992-, vol. 67 [2010], p. 144).

37 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Brand et al. 1983. On his sojourn in Sicily: Dufour 2013; Di Gennaro/Giannattasio 2015.

38 [Gerson 1942/1983] Schellinks most beautiful sheets are in the Atlas van der Hem in the National Library in Vienna. Compare also Gerson 1942/1983, p. 48. Schellinks travel journal, Copenhagen, vol. 3, p. 1076. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] A complete set of photographs of this travel journal is at the RKD .

39 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Gerson derived this information from Houbraken: ‘dat hy van Napels naar Rome, reisde in 't gezelschap der Heeren F. Kersseboom, en G. Sabé, en de Konstschilders N. Donkers en Alex. Petit’ [he travelled from Napels to Rome in the company of the gentlemen F. Kersseboom, and G. Sabé, and the artists N. Donkers en Alex. Petit] (Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2, p. 268). Hoogewerff already suggested that ‘Alex. Petit’ was probably not Alexander le Petit, as he died 1658/9, but his nephew Philips le Petit (c. 1631/2-1669/1673). Hoogewerff 1952, p. 141. Hoogewerff identified ‘N. Donkers’ with Pieter Donker (c. 1635-1668) (Hoogewerff 1952, p. 135).

40 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Houbraken 1718-1821, vol. 2, p. 179. Schatborn assumes that Houbraken was right and suggests that even the 58 ‘views from life in Italy’ (Paris, Fondation Custodia, inv.no. 6481) are probably all copies after drawings from life by Jan de Bisschop (Schatborn 2001, p. 199). The album is completely listed in (RKDimages 257780).

41 [Gerson 1942/1983] Somewhat later, in 1671, the Paradigmata graphices rariorium artificum. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] De Bisschop 1668-1669; Van Gelder/Jost 1985; Jellema/Plomp 1992-1993.

42 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] As far as we know, Jacob Neefs and Nicolaes Willingh never went to Italy. Of the first 50 etchings of the series, 17 are done after drawings of Willem Doudijns and six after Adriaen Backer (Jellema/Plomp 1992, p. 48). For the use of the material gathered earlier in the 17th century by Jacob Matham: Van Gelder/Jost 1985, vol. 1, ad indicem.

43 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] In 2001 Schatborn made clear that De Bisschop probably never set a foot in Italy and that he copied his Italian views after other artists, especially his teacher Bartholomeus Breenbergh (Schatborn 2001, p. 197-198).

44 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Cruyl: Jatta 1994.

45 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] The topographical drawings Gerson mentions are not by Michiel van Overbeek, but by the Monogrammist MVO , traditionally called Michiel van Overbeek, but not identical to Michiel van Overbeek (1670-1729), the cousin of Bonaventura van Overbeek who published prints after Bonaventura's drawings of the principal monuments of Rome in 1708. Also not identical to the collector Mattheus van Overbeek (1584-1638). The name of the present artist is derived from the monogram MVO on the back of a number of sheets; nothing else indicates that the name of the draughtsman in full should read Michiel van Overbeek.

46 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Orlandi 1704, p. 250, notes Isaac de Moucheron’s presence in Bologna in 1695. In and around Bologna he made several drawings before continuing his travel to Rome. On his Italian journey: Zwollo 1973, p. 39 ff.; Wedde 1996, vol. 1, p. 33-42. It is often assumed that Isaac de Moucheron provided Arnold Houbraken with much information on the Roman art scene at the end of the 17th century, but Houbraken omitted to dwell on de Moucheron’s activities in the Eternal City (Ibid., p. 42).

47 [Gerson 1942/1983] In the auction of Van Swoll of 22 April 1699, no. 86: A pagan sacrifice scene by de Moucheron after Poussin painted in Italy (Hofstede de Groot 1893, p. 148)[RKDexcerpts 350169].

48 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] None of them ever went to Italy, as is generally assumed today.

49 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] For the literature Gerson used for van Wittel, see note 56. Several monographs and studies bear witness to van Wittel’s central role in the development of the painted veduta: Briganti 1996; Strinati et al. 2002 -2003; Landsman 2018, Rozemond et al. 2019.

50 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hoogewerff 1920, p. 88-90. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On Meijer: Van Berkel 2000. On the dynamics of the cooperation between Meijer and Van Wittel: Witte 2013.

51 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 3, p. 103. Hoogewerff 1952, p. 117.

52 [Gerson 1942/1983] To judge from some Roman views, Gerrit Berckheyde must have been in Italy as well. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Gerrit and his brother Job went to Germany and came as far as Heidelberg. Based on Houbraken's report, and given the numerous years for which the presence of the Berckheyde brothers is documented in Haarlem, it is highly unlikely that Gerrit would have made any later journey abroad. According to Houbraken, the brothers longed for home when they were in Germany and decided to return instantaneously (Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 3, p. 196).

53 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Laureati 2002-2003.

54 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Van Wittel worked for Don Louis de la Cerda de Cordoba, Duke of Medinaceli (1660-1711) in Napels from 1699 until 1702. About van Wittel’s commissions in Napels, also for other collectors: E. Kolk in Rozemond et al. 2019, p. 76-79.

55 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Briganti 1996, p. 305-306, cat.nos. D11-D19, mostly from the collection of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi.

56 [Gerson 1942/1983] On van Wittel: Lorenzetti 1934; Voss 1926; H. Voss in Vienna 1937, p. 12-13; Fritzsche 1936, p. 22; Hind 1926; Buscaroli 1935, p. 87-88; Hind 1926A; Gerstenberg 1931; Smith 1939.

57 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] This applies even more to Hendrik Frans van Lint (1684-1763) (see below), who according to Houbraken went to Rome together with Wilkens.