2.3 The Dutch in Rome: the Bent and the Academy

With each year that passed the Dutch became increasingly involved in everyday life in Rome and so it is perhaps opportune to make a few remarks at this juncture about the activities they engaged in. Rome was their main destination. Regardless of whether they arrived overland via France (Paris, Lyon, Mont Cenis), as Wybrand de Geest II, Karel Dujardin, Jan Asselijn and Frederik de Moucheron among others did, whether they took the a boat from Marseilles to Livorno or travelled up the River Rhine to Basle or just to Mainz – in the first instance to proceed on foot over the Graubünden passes and in the second instance to proceed via the Tyrolean passes – all the roads they took ultimately led them to Rome.1 We will make a few remarks below about the Dutch artists who settled in Venice, Florence and at other courts in Italy, but it was to the Eternal City that the vast majority headed.

They crossed the River Tiber at Ponte Molle and walked down Via Flaminia before entering the city through Porta del Popolo [1]. Most of the Dutch artists settled in the adjacent quarter, which is bounded by the parish of Santa Maria del Popolo, San Lorenzo in Lucina and Sant’Andrea delle Fratte. Large numbers of them were to be found in Via Margutta, in Via del Babuino (which was called Via Paolina up to around 1625), in the Corso and in the narrow side streets and alleyways. This was the real foreigners’ district where the French painters and non-Romans felt at home.2 During the day, however, the young artists could have been seen everywhere in Rome: at the Forum, at the Colosseum, somewhere along the banks of the Tiber, at the Vatican, at Castel Sant’Angelo and outside the city boundaries in the catacombs or in the Campagna. Lake Bracciano [2],3 which the artists would have seen on their journey to Rome, was a favourite place for them to visit plus, above all, Tivoli [3] and the villages situated higher up above the River Anio such as Anticoli, Saracinesco and Subiaco. The Alban Hills and Frascati seem to have been frequented less often at that time.

1

Anonymous Netherlands (hist. region)

Rome, the the Mura Aureliane at the Porta del Popolo as seen from the east, with left the dome of Santa Maria del Popolo

2

Bartholomeus Breenbergh

Travelers on a hilly road near Bomarzo, 1629

Chapel Hill (North Carolina), Ackland Art Museum, inv./cat.nr. 2017.1.14

3

Jan Asselijn

Tivoli

Hamburg, Hamburger Kunsthalle, inv./cat.nr. 1963/116

The Dutch mostly made the long journey in pairs or groups and when they arrived in Rome they immediately entered the studio of an older fellow countryman. 4 In Florence and Venice they quite often worked in the studio of a local artist. 5 In Rome they preferred their own company, which was in keeping with their different attitude to art. In many cases they took lodgings together: Baburen and David de Haen, who worked together in San Pietro di Montorio, shared an apartment, for instance. Wouter Crabeth II moved in for a lengthy stay with Leonaert Bramer. These examples could easily be extended. Pieter van Laer took up accommodation for a while with the Fleming, Giovanni del Campo (c. 1600-after 1638) (perhaps a Jan van de Velde?),6 and was joined there by Gerard van Kuijl (1604-1673)7 and others. They replaced a tenant who had been obliged to move out because he was leaving Rome. These three even employed their own servant.

It was not long before all the Dutch artists joined together to set up a colony. In the beginning this ‘Bent’ (fraternity) was very probably no more than an informal, sociable gathering, but events led to a consolidation of the artists’ sense of community and the formation of closer ties between them.8 An initial circle must have formed in about 1620/1 around Cornelis van Poelenburch, Bartholomeus Breenbergh, Wybrand de Geest and a few less well-known painters. Jan van Bijlert has preserved the portraits of the founders of the ‘Bent’ for posterity in five drawings which are now in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam [4-8]. They all appear with their ‘Bent’ names, which were not exactly flattering. Interestingly enough, Pieter van Laer was not among them – a circumstance which permits us to date the drawings to before 1626, the year in which van Laer arrived in Rome.9

4

Anonymous ca. 1623-1624

Portraits of mmber of the Schilerbent in Rome, ca. 1623-1624

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

5

Anonymous ca. 1623-1624

Portraits of eleven members of the Schildersbent in Rome, ca. 1623-1624

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 8E

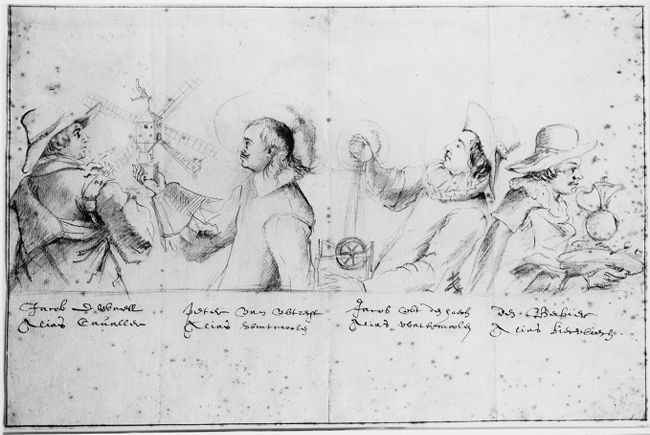

6

Anonymous ca. 1623-1624

Portraits of Giovanni di Filippo del Campo (c. 1600-after 1638), Pieter Anthonisz. van Groenewegen (c. 1600-1658), Joost Campen (1595-after 1640) and Simon Ardé (c. 1595-1638), members of the Schildersbent in Rome, ca. 1623-1624

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 8C

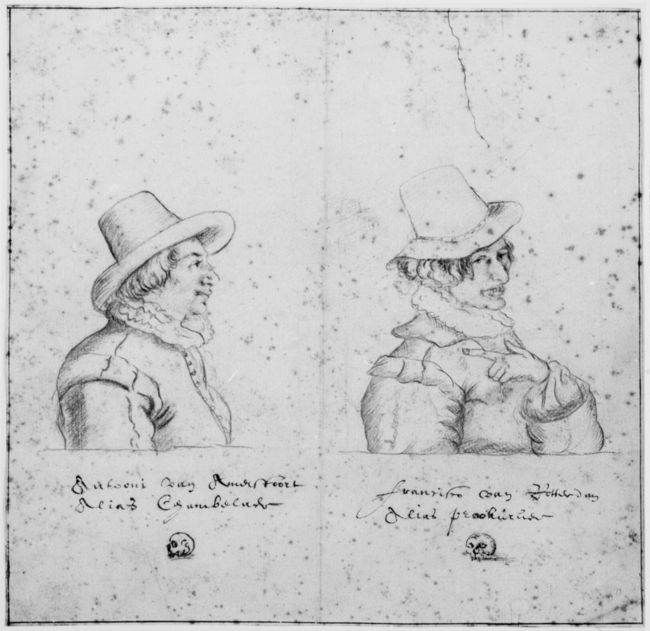

7

Anonymous c. 1623-1624

Portraits of Antonie Schouten van Amersfoort (?-1621/'23) and Frans Viruly (1594-1623), members of the Schildersbent in Rome, c. 1623-1624

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 8A

8

Anonymous ca. 1623-1624

Portraits of Jacob de Wael (?-?), Peter van Utrecht (unidentified), Jacob from The Hague (idem) and Dirck van Baburen (c. 1594/95-1624), members of the Schildersbent in Rome, ca. 1623-1624

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 8D

Sooner or later the ‘Bent’ had to come to some sort of arrangement with the official organisation of Italian artists, which needless to say was an academy, the Academia di San Luca, founded in 1593. At first the Dutch artists mocked the rules and ceremonies of the Academia. This took the form of strange customs within the ‘Bent’ involving a wine christening, a knightly accolade and a vow. The ‘Bent’ names also had their origins in a consuming desire to ridicule.10 All these customs notwithstanding, there was ultimately no way the Dutch artists could avoid certain demands raised by the Academia or undermine the privileges it enjoyed.11 For example, the Academy was entitled to value pictures and, from 1633, it had the right to require a contribution from all the artists living in Rome, including those from abroad who were not affiliated to any organisation.12 The Dutch were certainly at a disadvantage here, because the small figure paintings which had become fashionable since the days of Adam Elsheimer and Paulus Bril and which Italian customers were happy to buy could never – in the eyes of the representatives of official art – be placed on a par with great history paintings. Quite correctly from its point of view, the Academy feared a decline in art and its own reputation if it were to allow such common scenes portraying ordinary people into the temple of high art. A hint of professional jealousy may also have played a part. For the Academy no words could be scathing enough to express its repudiation of the paintings by Dutch artists. The conflict came to a head over a trivial matter, the Dutch refusing to pay the modest contribution required of them. From 1634 onwards nothing more was paid. However, despite an authorisation granted to the Academy’s treasurer in 1635 and the issuing of compulsory orders, very little changed and so this can certainly be seen as a defeat for the Academy.13 Later on, in the second half of the century, a settlement was gradually reached since there was no longer such a sharp division between the two communities over artistic ideals. The ‘Bent’’s heyday between 1640 and 1660 was followed by a setback and a decline in the creative powers of its members. Life in the ‘Bent’ consequently came to revolve around celebrations and drunken feasts. The christening ceremonies [9-11] at the grave of Bacchus (Santa Constanza) prompted the Inquisition to intervene, since it suspected that a Christian sacrament was being ridiculed. In the end, Pope Clement XI unceremoniously banned all celebrations and gatherings in 1720 unless special permission had been given.14

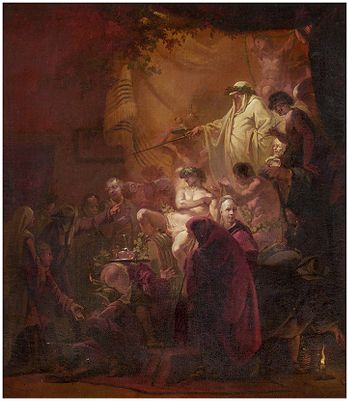

9

Domenicus van Wijnen

Initiation of a member at the Schildersbent in Rome

Private collection

10

Matthijs Pool after Domenicus van Wijnen

Inauguration of a member at the Schildersbent in Rome, before 1708

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1922,0410.267

11

Anonymous Northern Netherlands (hist. region) c. 1665-1670

Initiation of a member at the Schildersbent in Rome (?), c. 1665-1670

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-A-4672

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] Compare Hofstede de Groot 1927, Stelling-Michaud 1937, p. 14-15. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On the travel routes to Italy, see § 1, note 1.

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] G.J. Hoogewerff published the ‘status animarum’ and some registers of the parish of Sta. Maria del Popolo in Hoogewerff 1938. His publication regarding the archive of San Lorenzo in Lucina could unfortunately not be considered anymore (Hoogewerff 1939). [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] For the years 1600-1630: Vodret 2011. On Dutch and Flemish artist in Via Margutta: Hoogewerff 1953; Cappelletti 2012. For artists living in the parish of Sant’Andrea delle Fratte in the second half of the 17th century: Bartoni 2012.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] See the lovely drawing of 1629 [1627] in the collection of Mr. N. Beets (Hoogewerff 1929, p. 163). [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] illustrated above, see RKDimages 253609.

4 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Compare Pomponi 2011, p. 137-139; Sapori 2017, p. 190-192. On travel companions: Pomponi 2011, p. 140-141.

5 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] This is particurly evident in 16th- century Venice. Several painters from Northern Europe were active in the workshops of Titian and Tintoretto. See Meijer 1999A and Meijer 1999B. On Titian’s workshops: Tagliaferro/Aikema 2000.

6 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Hoogewerff 1942, p. 27.

7 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] The Gorkum painter Gerard van Kuijl has been confused for centuries with Gijsbrecht (Gysbert) van der Kuyl from Gouda (Sluijter 1977, Tissink/De Wit 1987, p. 26), of whom it is not known whether he was a painter. Van Kuijl's Bentnaam was 'Stijgbeugel' [Stirrup] (Hoogewerff 1952). Erroneously named Gerard van Krick by Sandrart (Von Sandrart/Klemm 1675/1994).

8 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On the Bent: Hoogewerff 1952; Levine 1990; Verberne 2001; Janssens 2001; Brown 2002; Geissler 2003; Cappelletti/Lemoine 2014-2015 .

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Obreen 1877-1890, vol. p. 298-307, Hoogewerff 1915. The attribution by Hoogewerff to Jan van Bijlert is uncertain. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Van der Sman in Cappelletti/Lemoine 2014-2015, p. 148-153 (by an anonymous draughtsman and datable to 1623-1624, on the basis of the portraits included).

10 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hoogewerff 1923. [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Hoogewerff 1952.

11 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] On the functioning of the Accademia di San Luca and its attempts to regulate the art market: Cavazzini 2008B, p. 43-48, 137-138.

12 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Hoogewerff 1952, p. 63.

13 [Leeuwen/Sman 2019] Hoogewerff 1952, p. 67.

14 [Gerson 1942/1983] Hoogewerff 1926. A good resume of Hoogewerff et al. is to be found in Vaes 1936. See also Noack 1927, vol. 1, p. 135-138. About the life in the Bent we have numerous sources (all listed and evaluated in Hoogewerff’s publications), of which only the most important ones can be named here. Most of the Bent-names together with their interpretations can be found in Van Ryssen 1704-1708/1719, p. 135-152. Arnold van Houbraken cites the poem (Houbraken 1718-1721, vol. 2, p. 348). Dominicus van Wijnen (1661-1698) painted the ceremonies around the admission of a new member, which were engraved by Matthijs Pool (1676-1740). These paintings were made for the archeologist Bonaventura van Overbeek (1660-1705). The description of such an admission party we owe to Cornelis de Bruyn (1652-1726/7).